ADS

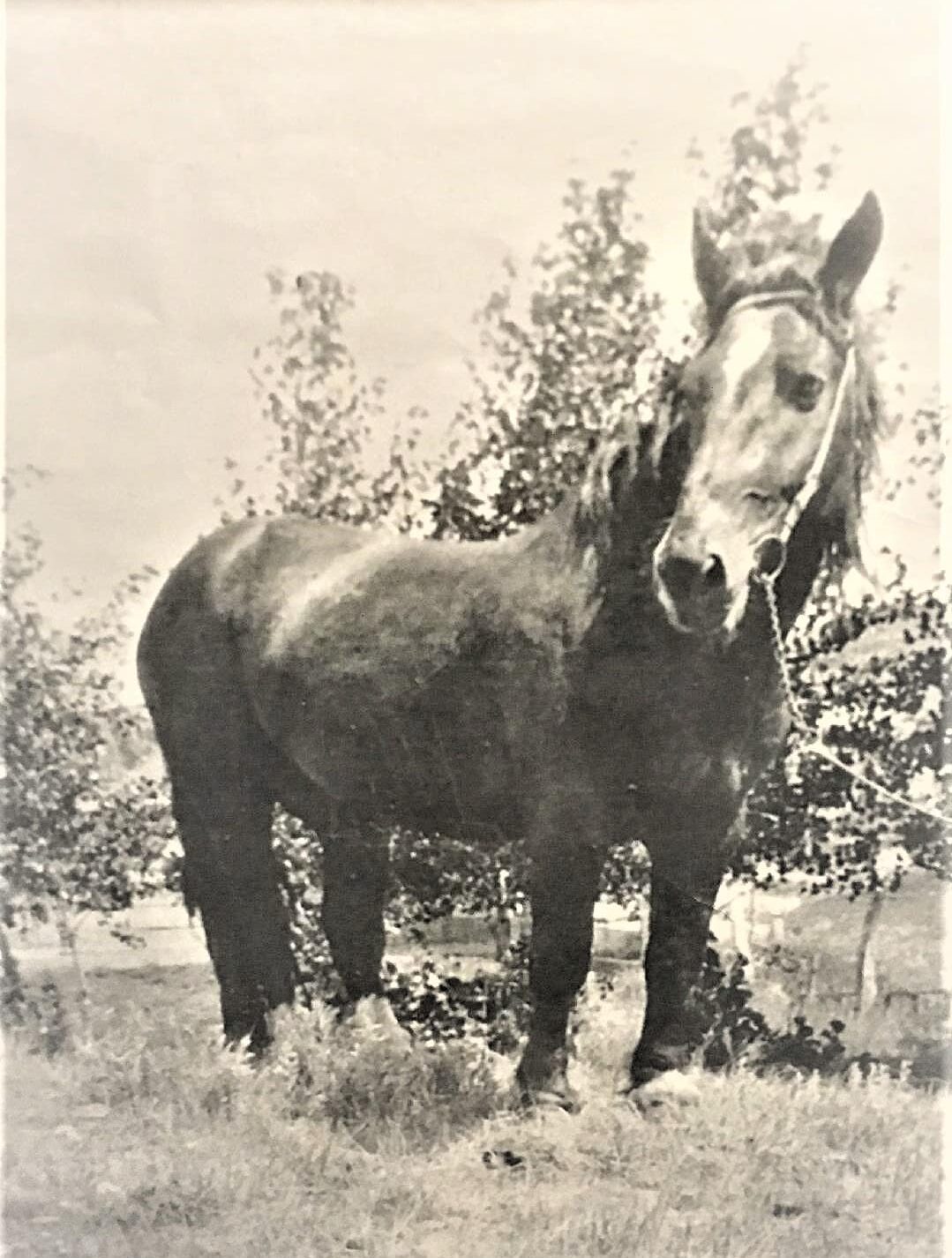

Rex [Photo: Martell Family Archives]

Where in this wide world can man find nobility without pride, friendship without envy, or beauty without vanity?

– from “The Horse” by Ronald Duncan

Rex was indeed noble — in stature and disposition, but he was not haughty or conceited. He knew without fail what to do and how to do it. He was willing and steadfast. Rex was a magnificent stallion standing sixteen hands high. A sorrel, his coat was a deep rich copper that shined with a golden luster when the summer sun shone on him after he first shed his winter coat.

Franklin was a horseman. When he was a young man before coming west, you would find him on horseback driving cattle around the farms of New York, quite the unusual sight. It did not take long for his natural abilities to be fully realized once he made his way to western North Dakota. He became well-known as an exceptional judge and trainer of horses and would be called upon by neighbors for his skills and knowledge. Franklin knew and understood horses. If a horse acted up, he would say, “There’s nothing the matter with that horse, he just needs a rider.”

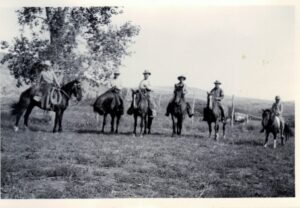

C. F. Martell (Franklin) on Rex [Photo: Martell Family Archives]

By 1913 Franklin was running several hundred head of horses. Each spring Franklin and the hired men rode out to the place they called Horse Camp to bring in the herd. Horse Camp was down in the badlands of the Little Missouri River about 25 miles south of Franklin’s ranch. Every year they had a late spring roundup with thirty to forty cowboys lasting several days. Franklin said, “The cowboys were good, and the riding was hard over rough country. The horses would be wild having been loose for six months.”

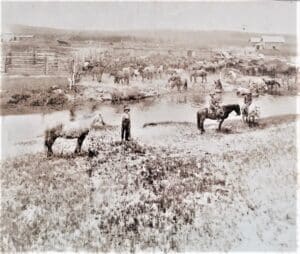

[Photo: Martell Family Archives]

Over the years, he watched his horses as foals and yearlings. When they were two-year olds, it was time for them to be broken and trained. Franklin inevitably and instinctively knew which horse was going to be best for which job. Bringing them into the corral, Franklin would look them over and single out the ones he thought would be worth working with. After they were broken, most went to nearby markets for local ranchers and farmers. Others more suited for work in the cotton fields were sent south. The good buckers became rodeo stock. Later in the 1920s when the horse market in the Midwest was faltering, Franklin sent his horses to the still prospering eastern markets. Rex came from this corral.

[Photo: Martell Family Archives]

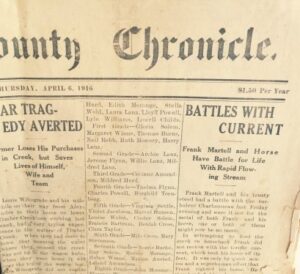

Franklin had many horses, but two held a particularly special place in his heart. A pinto mare, his payment for his first fall working out west, was his most prized possession. She was given to him unbroken and in those early years became a real friend and partner. This little mare was credited with helping him survive a “battle royal of man and beast against the current and ice crust which was still on the water in places,” as they attempted to cross a treacherous Charbonneau Creek in the spring of 1916.

[Photo: Martell Family Archives]

And then there was Rex, who became the most favored of all. Rex could do everything; he was a cutting horse and a roping horse — an exceptional all-around cow pony. He could be counted on for whatever was needed. Franklin knew Rex demanded respect of his rider, but Rex also knew his manners. Franklin trusted Rex with what was of the greatest importance, his children. Bonds of loyalty, trust, even friendship had been forged.

Martell’s daughter, Helen, on Rex [Photo: Martell Family Archives]

One of Franklin’s four girls recounted two times Rex came to her rescue. As was usually the case, children growing up on a ranch were expected to work. Generally speaking, the cattle work fell to the older brother. One day help was needed rounding up some cattle and bringing them into the yard. By this time Rex was not worked very hard, but he was still reliable. Up in the saddle she went, a little apprehensive because she was not sure what was expected. While she bounced around in the saddle, Rex without direction knew what to do and just did it. If a cow and calf were separated, off they went; Rex loved the chase! Whatever was needed Rex accomplished it.

Near the Creek [Photo: Martell Family Archives]

Often in the spring Charbonneau Creek would flood and driving to town to pick up the mail was not possible. Usually, Franklin or a hired man would go, but one spring day there was no one available; Franklin’s girl thought it would be fun to get out of the house and ride into town, so she volunteered. Now Franklin was pretty certain she didn’t know which way to go and might lose her way, but she was insistent, and he knew Rex would be her ride. Out of the yard she rode, through the first gate and over the first hill. Looking around she soon realized she was not sure which way to go and became worried. She did not need to be, Rex knew where to go and made the right decisions to get them the six miles safely to the post office and back home.

Horse Herd [Photo: Martell Family Archives]

Franklin rode Rex as long as he could, and when he was too old to be ridden or worked the way a ranch horse needed to be, he was pastured close by the house and family, living out the rest of his days in this pasture of honor.

Mary Pat’s father grew up on a ranch near Charbonneau, North Dakota, where his father began homesteading in 1908. She spent many childhood summers visiting her grandfather C.F. Martell and enjoying life in Western North Dakota. She is incredibly proud of her heritage and is dedicated to the preservation of North Dakota history and the western way of life. Mary Pat serves as a District 13 trustee for the North Dakota Cowboy Hall of Fame (NDCHF) and is a frequent contributor to their publication, The Cowboy Chronicle. She is also contributor to North Dakota Horizons magazine and Minot Daily News. She enjoys her work on the board of directors for the Lewis and Clark Trail Museum in Alexander, North Dakota, where numerous items from the old Martell Ranch can be found. She currently lives in California with her husband of 45 years, their five children, children-in-law, and 10 grandchildren.